Chinese Millennials and Gen Zers Take the World’s Stage

Conversation with Zak Dychtwald, Author of Young China: How the Restless Generation Will Change Their Country and the World

By Stephen Dupont, APR

When we think about the next ten, 20 or 30 years, I, like many Americans, think about the world in terms of how the United States will lead in areas such as culture influence and technological innovation.

In his new book, Young China, Zakary Dychtwald says that would be a mistake. Because the world as we know it is likely to experience a seismic shift due to the sheer gravity of one key factor – the more than 417 million Chinese people who belong to the Millennial and Generation Z generations.

I had the opportunity to speak with Zak twice recently about why he believes China’s Millennials and Gen Zers are ready for their turn on the world’s stage and what the impact of their efforts in redefining such things as day-to-day culture and technology (artificial intelligence, clean energy, space travel) may mean for America and the world.

If you do nothing else, do this: Shy of learning Mandarin Chinese, take the time to start learning more about America’s #1 trading partner and its #1 competitor in the world.

Stephen Dupont: Zak, why China? Why did you decide to study Chinese Millennials and Generation Zers, and write a book about them?

Zak Dychtwald: To answer that, I need to step back about why I ended up writing a book in the first place. I had no intention of writing a book when I went to China. But, what ultimately drove me to write the book was that as I was getting to know, on a deep level, a group of people in the world, whom I felt were pretty misunderstood, I felt compelled to write a book about them — the young China that I came to know.

What struck me was the way that people in the West chose to characterize China – its government, its economy, its culture and its people. I noticed a lot of catastrophe-driven news stories, for example. It became clear to me that those news stories did not reflect what was happening with Chinese younger generation, who I felt were defining China’s modern identity.

I see a China on the rise, and that this young generation is coming to embody it and represent it on the world stage. As I was immersing myself into its culture, I read every book I could find about China to understand who they actually are, what matters to them, how they see the world, how they see themselves, and how they see their future. But as I was reading and comparing what I was actually seeing day-to-day while living there, I saw this massive gap in the understanding of the people. What I really wanted was to write a book that I wanted to read.

So, with the encouragement of my Chinese friends – really with the strong encouragement of them, because I was not super excited about the prospect of writing a book, but recognizing that there was a real need, a real want, and that I could be one of the people to do it, ended up pushing me to write this book.

Stephen Dupont: So, could you dig a bit deeper into that question, Zak. As I understand it, you’ve become fluent in Mandarin Chinese, is that right?

Zak Dychtwald: Yes.

Stephen Dupont: How did your experience in learning Mandarin as well as living in China for several years — help you to understand the young Chinese mindset?

Zak Dychtwald: Well, I think of it as more of a mental diet. When I first went to China, I didn’t really speak the language, and I knew what I needed to do was immerse myself completely into the culture and the language in order to learn the fastest. So every single thing I did I tried to do in Chinese.

Stephen Dupont: But not all foreigners do what you do…

Zak Dychtwald: No they don’t, and this is a perspective to share with your readers. When you move to China as a foreigner, that does not mean immersion in the culture. There are bastions of foreign people in every city – an international community that does not necessarily want to dive in head first into the Chinese culture.

So, the music I listened to, the language on my phone and my computer, the TV I watched, the movies I watched, the podcasts I listened to, the friendships I had, the roommates I had, the dates I went on – which started painfully awkward, but then evolved into something more complex – I did in Chinese. And not just learn the language but the culture.

I think we often use language to proxy a culture. China is so linguistically distant from English, and likewise, the culture is distant from that of Western Europe or the United States. So I felt that if I put all of my relationships, all of my information inputs, all of my fears, all of my wants, and all of my desires into the language of Chinese and I talked about them with my Chinese friends in their language, I’d be significantly closer to being able to understand how young people in China see their country and the world.

It was a level of immersion that I was totally committed to. I didn’t realize it until afterwards, but it appears that this approach is relatively unique. But to me, that was the only way I knew how to do it.

Stephen Dupont: Do you go back to China often?

Zak Dychtwald: I was there full time for four years, and when I returned, I would spend about half my year in the United States and a third a year in China. I recently made the decision to move back to China on a more full-time basis and invert those proportions. There is a lot of travel in my future, as I really want to be bridging one place to the other effectively.

Stephen Dupont: China, like the United States, is a big country where 500 or more dialects are spoken, so I’m told. America is a patchwork of people — we have the people in the Deep South, the Midwest, the Northeast, Silicon Valley. China has multiple cultures represented within its country. Did you happen to focus on a particular area or region of China to get to know the country? Does Shanghai represent the face of China?

Zak Dychtwald: There’s something that I refer to called the Shanghai Fallacy. It’s that when most people visit China, they go to Shanghai. They look at the city, at all of the foreign restaurants, the styles that people are wearing, and they have an English-speaking guide who shows them around the French Quarter and all the things that are kind of comfortable for them.

A lot of these people are only seeing things and people with whom they can interact with in English, so that’s the version they’re getting and sharing with their co-workers, friends and family when they return home.

When they see Shanghai, they think: “Modernization means Westernization.” In other words, the process of China becoming a modern country — a modern power — means sliding into the Western model. Not just politically or economically, but culturally in terms of what they like to wear, eat, or watch on TV – that it’s all going to be Westernized all over China.

In reality, Shanghai is the least representative city in China. Shanghai did Westernize as it modernized, and it’s the only city to do that in China, period. Beijing is not that way, Guangzhou and Shenzhen are not that way, and Chengdu is not that way.

So, to answer your question, what I tried to do is focus on emerging second-tier cities as part of my immersion into Chinese culture — cities such as Suzhou and Changzhou, for example.

It used to be that if I was from Guangzhou versus Chengdu, I would encounter a different dialect of Chinese in each of those two cities. This is true of anywhere you go in the world — if a culture is isolated long enough, it develops its own lingo or dialect. It makes sense that where you were from was the most defining characteristic in terms of who you are or how you defined yourself as a person.

But, bizarrely — and this is at the core of my book — that’s become less the case anymore. For the first time in 5,000 years of Chinese history, it’s no longer where you are from within China that defines you, but what generation you are from.

It used to be that it was very difficult for Chinese from one province or one city to interact with people from other towns, because they all used to speak different dialects. But now, everyone speaks Mandarin, so there’s been this homogenization occurring throughout the country. When you are from, not where you are from, is now the most defining characteristic.

Stephen Dupont: What about the movement of more Chinese from the countryside to cities?

Zak Dychtwald: Yes, that’s another important factor that is redefining China. There has been this massive urbanization push — hundreds of millions of people who have, and continue to, move from rural China to urban China.

Who’s moving? It’s mostly what you and I would call Millennials and Generation Z Chinese. Young people from small towns all over the country are pouring into big cities. And so it’s again, less about where you’re from and more about when you’re from, because if you’re a young person, you’re likely in a city, now. Which is, again, the first time ever in Chinese history. And so, you have, because of the Internet, because of WeChat (China’s most popular social app, which has broad functionality and boasts 1 billion users) because of the common language, because of TV shows, which Chinese can now watch at the same time throughout the country, you have more homogeneity within China than ever before.

In 1911, Sun Yat-sen, the father of modern China, described China as a sheet of loose sand — a lot of disparate nodes that were sort of on the same holding receptacle.

The project of modern China, over the last 100 years, in a lot of ways, has been linking the country together to create a more modern version of a unified China. So having the same language, an infrastructure program that links the entire country through railways, and the Internet, are all part of this ongoing process of unifying China.

This is the cool part when I think about China’s Millennials — they’re starting a modern Chinese culture. There’s an emerging Millennial mindset within China about what it means to be Chinese in the modern world, so not just what it’s always meant to be Chinese, but what it means today. And that’s happening now. So while it’s important for each city to have its own identity, this new mindset is developing irrespective of location, and more across generational lines.

Stephen Dupont: In the United States, much has been written about American Millennials, and now you’re seeing a lot of articles about Gen Zers, and the articles are talking about what they want, what they want for their lives, what they want for their country, what they want for work. Do Chinese Millennials and Chinese Gen Zers want a lot of what American Millennials and Gen Zers want? Or is it something different?

Zak Dychtwald: Chinese Millennials and Gen Zers want something different than their Western counterparts. I think Americans need to recognize that young Chinese grew up with their own environment, their own cultural backdrop, and with their own set of economic pressures.

Remember, in 1993, the per capita GDP in China was around $377 per year. Today’s young Chinese have watched their country transition from extreme poverty to moderate wealth in their lifetime. Millennials in the United States, on the other hand, have for the most part, have grown up in moderate wealth, and we remain a wealthy nation. If environment matters for a generation growing up — which I believe it does – then I would say you have young people who are about the same age, but have very different experiences, and therefore, want different things from life.

A big part of the difference has to do with the identity of Chinese Millennials. They want to be seen as unique, they want to be recognized as not just wanting to be like American Millennials but with different haircuts. They want to be recognized for their own individual identity as a culture, and as a nation, rather than just American wannabes.

On top of that, Chinese Millennials have a major want for freedom. But it’s not how you and I, as Americans see freedom.

Stephen Dupont: By the way Zak, how many Chinese Millennials are there?

Zak Dychtwald: That is an important question. Here’s why: In the United States, there are about 89 million Millennials. In China, there are 417 million Chinese Millennials. Think about that – that’s more than the entire population of the U.S. and Canada combined. For your reference, there are more Millennials in China than there are Millennials in North America, Europe, and the Middle East combined.

Stephen Dupont: What about India?

Zak Dychtwald: India is the only other country that has nearly the same number of Millennials as China, however, India does not have nearly the same economic and political clout as China as a whole, or as this young generation has.

So, when you talk about impact, Chinese Millennials are having, and will continue to have, an enormous impact on their own country, as well as on the world, simply because of the sheer number of them.

Let me put it in another way: If you’re wondering who you’re little Johnny or Jennifer is going to be competing with to get into the best universities, to get the best jobs, or to buy the best homes, it’s going to be a Chinese Millennial.

Stephen Dupont: What’s the difference between how Chinese Millennials were raised compared to American Millennials? What do you think has been the influence of the different ways that they were raised on each group’s approach to the future?

Zak Dychtwald: Millennial Chinese, as well as Generation Z Chinese, face enormous pressure. The way that youth are raised in China is fundamentally different than in America and many other Western countries.

It boils down to one test, the Gaokao — the country’s college entrance exam. In the United States, we have this ideal of raising well-rounded children and a shared vision that, “I can be the captain of the speech and debate team; I can be on the swim team, and all of that will help me get into a good college.” And, by in large, our system recognizes that as important.

But in China, there is only one determining factor in terms of how you get into college, and that’s the Gaokao.

So, when I’m five and I’m at a sleepover with my friends here in the United States, my peer in China is studying for that test.

When I am at swim practice in the morning before going to high school, my peer in China is in the library studying.

If you are the captain of the cheerleading team, that’s great, but your peer in China is studying.

There’s a study culture that dominates everything as a young person in China, and so it leads to a pressured lifestyle that we can’t really fathom.

Let me share a story with you…

I was teaching English in China during my first eight months in the country. I was teaching a kind of well-to-do class on the weekend where technology was emphasized, such as coding. So there was a group of five kids in my class who were about five or six years old. We also had two teaching aides and one foreign teacher. There was this boy I remember who had these sneakers that lit up whenever you stepped on the heels. He was an absolutely adorable kid.

What was different about this class was there was a glass partition where 10 parents and 20 grandparents (China’s 4-2-1 demographics: 4 grandparents for every 2 parents for every 1 child) were watching the class. So you had 30 adults watching every click of a microscope, every pound of a keyboard, and every twist of a robot that these young kids, that the five children were doing in the class.

When the class was done, I went out to talk with the parents. I noticed in a corner of the room this particular little boy with the light-up sneakers surrounded by his parents and grandparents and he was crying. His mother and his grandmother were in front of him showing him what appeared to be a notebook full of paper. As I approached, I see on the pieces of paper all of the words we studied that day – microscope, seashell, dolphin, robot – written in English. His grandmother and his mother are quizzing the boy. I asked, “What’s going on?” as I didn’t assign any homework. The boy’s mother says back to me: “Our son will have to take the Gaokao college entrance exam in 13 years. We’re trying to give him the edge.”

Stephen Dupont: Was that normal? I mean, did you see other parents putting that type of pressure on their kids?

Zak Dychtwald: That wasn’t unique. The competition in Chinese society for a position in a private high school and for a position in a good college is unbelievable. To get into the best schools in China, it’s not, like, how many per 100, it’s many per 10,000 are admitted. But the impact goes beyond that to the competition to get a top job and to marry. The level of competition within China is fierce, and it leads to a type of childhood that we can’t understand.

The other factor in all of this is pride. This young generation in China has watched their country, their family, and themselves grow wealthy and rise into a position of power faster and larger than any other cohort or country in the history of the world. They feel they have a lot to be proud of.

Stephen Dupont: Can you add some context to that?

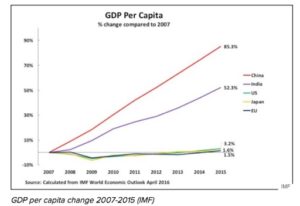

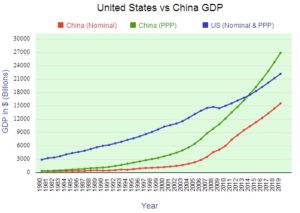

Zak Dychtwald: Yes. Think about it in this way. In my lifetime, the U.S. GDP has grown 2.5 times since I was born in 1990. So, generally speaking, the things we can buy and the places we can go is about 2.5 times better today than it was in 1990. But in China, for that same period, the GDP has grown 27 times. (Note: These statistics are calculated using World Bank statistics on per capita GDP, 1990-2017.)

How does that compare to other countries? India’s growth is just over 5x; Brazil is 3.2x; Germany is 2.0x. The point is: what China’s population has witnessed over the past 30 years is unprecedented in modern history. Isn’t it ironic that a country ruled by the Communist Party has created the most successful capitalistic revolution in the last 30 years – and really, actually, in the history of economics. There’s no precedent for what this young generation has witnessed. They’re becoming more aware of that and feel proud about what they’ve accomplished.

Here in America, we’re in a bit of an identity crisis, obviously. We elected a president who ran on the platform of making America great again, which sort of suggests that we don’t think we’re that great now. Obviously, American Millennials didn’t do the most of that voting, but there’s the real question of what is America’s role in the future. This young generation in China sees their country becoming more powerful, and taking on a leadership position in the world. They’re very proud of that.

Stephen Dupont: How has the amount of growth, and the creation of wealth that has been created in China over the past couple decades impacted the every day Chinese Millennial?

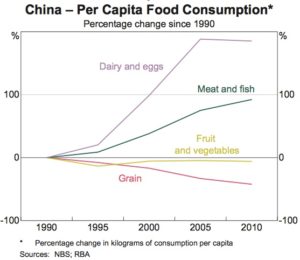

Zak Dychtwald: Here’s a good example. In 1990, there were a million or maybe two million electric refrigerators throughout China for more than a billion people. There were very few cars on the road because most Chinese biked to work. And even then, a bicycle was a luxury.

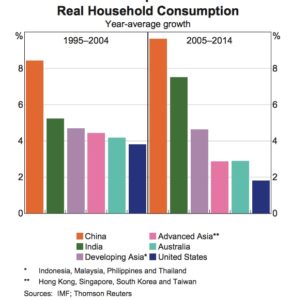

What I see happening today is what I call the “development of desire.” Here’s an entire nation, that is learning how to play versus learning how to survive. China, by the numbers, is the biggest foodie nation in the world. So, one of the first things that has changed as more Chinese Millennials have disposable income is the amount of time and money they’re spending on out. The amount of caloric intake for the average person in China has, compared to 60 years ago, fully doubled. And, they’re eating more meat. The amount of meat that the Chinese are eating has gone through the roof within the past decade. People say that you can tell China’s level of happiness by the price of pork that day.

Then there’s the amount of TV they’re watching, and the number of movies they’re going out to see. Right now, you can’t have a movie opening in Hollywood if it doesn’t have a second opening in Beijing. Movies serve as a way for the average Chinese to kick back and relax. You’re also seeing more people playing sports, too. So there’s a recognition that studying isn’t everything and that there should be the pursuit of a more well-rounded ecosystem.

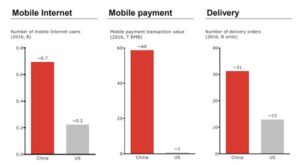

One easy way to look at this is the amount that Chinese spent online last year. Actually, let’s just look at mobile spend. According to Bain & Company, in the U.S., we spent 1 trillion CNY in 2016. In China, during that same year, consumers spent 60 trillion CNY, so, 60 to 1. The Chinese market has adapted to shorten the distance between want and have, and this is already far beyond what we have in the United States.

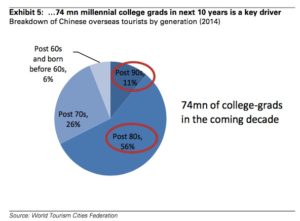

Here’s another interesting observation: Only nine percent of the county’s population of 1.379 billion has a passport, but two-thirds of those people who do have a passport in China are under the age of 37 – they’re Millennials.

So it’s a generation that wants to see the world, when their parents could not. There’s a tremendous desire to experience things – and this is, by the way, one of the overlaps between American Millennials and Chinese Millennials. Chinese Millennials are much more experience-driven in China than older generations – similar to what you’re seeing in the United States. By the way, this is something we learned from the Boomers; I would say there are more similarities between American Boomers and Chinese Millennials, in terms of what they signify culturally. There’s the want to individuate, there’s the want to sort of rebel from their parents. They’re both known as the “Me Generation,” they’re both known for being sort of selfish and wanting stuff, wanting to experience things, wanting to go to that concert, and wanting to think differently than the older generation.

To Chinese Millennials, it’s not about buying a Gucci belt. It’s about having an unforgettable trip and making lasting memories. This young generation in China, particularly because they grew up in such an insular nation for so long, is in this major exploratory phase. It’s pretty beautiful to watch.

Stephen Dupont: I recently attended a conference hosted by the World Future Society. Long-term planning was a discussion item and one of the speakers made the comparison between the Chinese government’s approach to thinking many years out, and the U.S. approach, which seems more reactionary – don’t do anything until a crisis comes along.

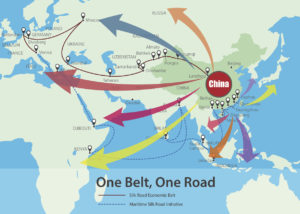

A good example of the Chinese approach is its $900 billion investment into the new Silk Road project, which will build an overland trading system between China and London.

So, do you think young Chinese Millennials and Generation Zers will continue with this long-term planning mindset even as they seek more freedom, and are exposed to other cultures through international travel?

Zak Dychtwald: There’s two different ways of looking at this question. The first is from a political perspective. From that viewpoint, there’s the argument that China is playing chess, and the U.S. is playing checkers. China thinks in generations, and I actually think to a certain degree, that plays out. I’ll speak more about that in a second.

China’s young generation is different than the older generation in China, which was defined by their ability to chiku [吃苦], or to eat bitter. It’s a word that means to endure and persevere through hardship while at the same time, to press forward. Or, to do difficult things for a long period of time at the prospect of delayed gratification. Which is sort of what you’re referring to when you think of the Chinese approach to long-term planning. It’s this idea that, “If I work hard for 20 years, and recognize that I’m not going get a payout until 20 years from now, I’m gonna have a better life, and more importantly, my kids are going to have a better life — the next generation will have a better life.

What’s so different between the young Chinese generation and the older generation is, while they still have that “eat bitter” mentality (again, remember, many Chinese Millennials were raised in poverty) they’re a tougher, harder-working generation than most global Millennials, with the exception of other East Asian cultures, especially Singapore and South Korea.

However, this younger generation in China has a far greater want than their parents to live in the moment, to experience and enjoy themselves now. With that, we’re starting to witness savings rates going down among young Chinese, and you’re seeing young Chinese talking with each other about the value of enjoying what they have today versus constantly putting off and planning for the future.

Stephen Dupont: Can you speak to the young Chinese mindset about dealing with the United States? How do they see it?

Zak Dychtwald: So there’s now the perception that if you want a deal with the United States, it’s likely that every four years the deal will get torn up. The TPP (Trans-Pacific Partnership) is probably the best, most recent example, of that.

You referred to the new Silk Road project. It’s known as the Belt and Road Initiative, and there’s actually up to $7 trillion in funding for this. There’s more than 70 countries involved, so it’s not just Mongolia and Russia and the places around it, but like you said, it’s going to go all the way to London, and it will impact countries such as Kenya and Indonesia, too. It’s a massive initiative.

At a time where it looks like every four years the United States might tear up a deal, China is building its relationships in concrete and steel and in bridges and ports — to last not just every four years, not just every ten years, but to last generations. And from a political and economic standpoint, a lot of people, or a lot of countries, are recognizing that. They’re saying: “You know, I get that China has its own motivations, but it’s not aid, it’s not out of good will. They’re making an economic deal, a business deal, that we can understand, and we need the money. And I’d rather dance with China, recognizing that they’ll be in a similar place 10 or 15 years from now. Whereas, it’s hard to say where the U.S. will be in that same period of time.”

Stephen Dupont: So, our current U.S. administration seems to be basically overturning or dramatically changing a lot of our country’s long-time alliances, and seems to be pushing itself more toward Russia, which is our 30th largest trading partner. At the same time, the U.S. is antagonizing our largest trading partner, China, with tariffs. How do Chinese Millennials see this? Are they scratching their heads, like I am, wondering, “Why is the U.S. becoming more friendly with Russia when in fact, we are their number one trading partner?”

Zak Dychtwald: Here’s what it looks like from within China. First, it looks like President Trump is beholden to Russia in some way that we don’t yet understand. Because like you’re saying, it

just defies logic. There are variables that are not clear to the Chinese as to why Trump is favoring Russia. Because in terms of what evidence we have internationally — not just you and I — but from China – it looks like Trump clearly has a conflict of interest somewhere, and we can’t see it entirely.

But, let me speak in more broad terms. What the United States is doing to China is consistent with a long-held narrative, which is that the United States and the Western world is threatened by China and is intentionally trying to constrain its rise. So, by the way, this is in part propaganda — the Opium Wars (1839 – 1860) – which Chinese refer to now as “fù xīng,” [复兴] which means, a rejuvenation.

This rejuvenation means that China was once great. It was once the most powerful nation and empire in the world (in the early 1800s), and for about 1,000 years that was true. And then, at one point, it had a terrible fall, and it began with the Opium Wars (war with the British Empire). The Chinese see this as 100 Years of Humiliation, in which China allowed itself to become weak. It refused to have its own industrial revolution, and its own scientific revolution, while the rest of the world moved forward.

And at the same time, in this weakened state, the Western world took advantage of it. It made it intentionally weak by funneling opium into the country, and then sort of made it a half-colony in its own land. So, that is the narrative from within China: “We were once strong, we got weak, in part because of our own weaknesses and in part because of foreign aggression.” And now, what the United States is doing and what – and this is, again, part propaganda and part sort of just what it looks like – is it’s trying to continue to keep China down, to keep it from being a world power.

So, from a young Chinese’ point-of-view, it looks like what the United States is doing in terms of tariffs is blatant aggression. And that’s consistent with the U.S. just trying to protect its own power because it feels threatened by China.

Then, there’s another angle to this. The trade war sort of tacitly acknowledges is there is a growing equality between China and what they’ve always looked at as the major superpower in the world, which is the United States.

It’s similar to the nuclear power parity between the U.S. and the Soviet Union during the Cold War. Ten years ago, you couldn’t have had a trade war with China, based on China’s economy at that time. It wouldn’t have made sense.

So, as painful as the trade war is for China, and for us, too, there is a bit of pride, like, “Okay, we are now eye-to-eye with what has, for our entire childhood, been sort of the city on the hill, the foil for China’s development, which is the United States.”

That’s different. Again, it goes back to this pride thing. It’s suddenly, “Hey, you know what, we’re the number two duking it out with number one, and doing a pretty damn good job.” That’s a different mindset than 15 years ago.

Stephen Dupont: Zak, as you can see, most of my questions here have been focused on this perceived and real competition between China and the United States. But how do Chinese Millennials and Chinese Gen Zers look at their neighbors, such as the Millennials in Japan, Vietnam, South Korea, or their neighbors to the north such as Russia, and how do they see themselves in that sphere of the world?

Zak Dychtwald: That’s a great question. So, if you look at what influences the young generation in China, America is huge with its media exports, such as our music and media. But South Korea and Japan are also massive. South Korean soap operas, South Korean TV shows, South Korean K-pop, South Korean karaoke culture, has been a major influence on this young generation in China.

On top of that, there is a sort of an East-Asian kinship. It’s this idea that you want to see people people who look like you, represented on TV, and in the media. Oprah talks about it — the importance of seeing powerful, positive African American women and men in the media to creating role models for African-American children. To see South Koreans that create music, and style, and fashion, and TV shows, for young people in China, you know what, there’s a closeness there that they can’t imagine when looking non-Asian performers.

There’s a closeness between the East Asian cultures, that really isn’t there with Russia, definitely, or even with Southeast Asia. Southeast Asia, particularly countries such as Thailand, are places that China still sees as developing, they see as sort of poor and backwards compared to them. This goes back to this idea of pride — those places are still developing, they’re on the path that China forged, but China is the big player in the region.

Japan is interesting, because of the tormented history between Japan and China — particularly World War II and Japanese occupation. The young generation in China does not have that blind nationalism that Japan is evil as the older generation has.

That’s not to say that there aren’t people who feel that. Because there are. But among the more urban educated crowd it does not carry the same weight. As an aside, I understand this because I’m Jewish-American. When you read the textbooks in China, which go into the horrifying details of the Japanese occupation of China, you can see why the Chinese would feel like they do toward the Japanese. But with the younger generations, that level of animosity is lessening.

Stephen Dupont: There are a lot of people who are carefully watching China’s investments in artificial intelligence, space, and green energy. The narrative I’m hearing is that China is investing heavily in these areas, whereas, the United States seems to be almost, in the example of clean energy, turning its back on that entire industry.

How are Chinese Millennials, who are fully in the workforce, driving this focus on new technology and innovation?

Zak Dychtwald: The innovation and creativity of this younger generation in China is probably the biggest watershed difference between this generation and older generations.

The young generation has the capacity for innovation and creativity, and the older generation was generally seen to not have that. So how do they see innovation? They see it as the ticket to China’s future. This young generation will not be making the world’s shirts — that’s not what they will be doing. They’re forward-looking and they recognize there is major value to leadership.

They say to themselves and each other: “My family can get wealthy if I create something that is a new technology, or a new way of absorbing energy from the soil, or a new innovation from AI, or a new app that can change the supply chain.”

Those are the people who are making the news every day in China, and they are the role models that people are looking towards. They recognize that these people are changing their personal and family fortunes, as well as the course of the country.

So, there’s an enormous buzz, right now, in China around innovation and around startup culture. Part of that is just organic. Again, China, and particularly in the mobile space, is far ahead of where we are in the United States – especially in the blending of social and e-commerce. You know, I could order a pen, a computer, and a motorcycle in the morning, off of JingDong (JD.com) or Alibaba, and it’ll be there in the afternoon that day. There’s another level of how that’s integrated everything is becoming in China.

The other side of innovation involves government incentives.

In contrast, where Trump is focused on coal, in China that is a major signal, which to them says, “Okay, one of the biggest players in the world is shrinking away from this green energy. That’s an opportunity for us.” (Note: Read this article from the New York Times on China’s $360 billion investment into clean energy for further insight.)

Keep this in mind: China’s aging population combined with its single-child generation means that over time, China will not have enough people to support its manufacturing economy anymore. So they need to create more value per person. And the way to do that is with innovation. Green energy, for example, is for the Chinese government, an opportunity to escape the middle-income trap — the idea that developing nations get stuck as a moderately wealthy country.

The ability to be a leader in green energy, artificial intelligence, robotics or biotechnology, for China, are areas that the rest of the world is shrinking away from. Because of their government structure, they can incentivize their incredibly smart and hardworking population to solve some of those problems.

This is not just to help their national economy, but also to establish themselves as leaders in the international economy. In my opinion, many people don’t think of China as a creative force on the international sphere, or business sphere. There are some exceptions, such as Alibaba, Jingdong, Baidu and Tencent. But from a big picture point of view, what the Chinese government is trying to do, and what the population is getting behind, is to incentivize the next generation of Chinese business, economic, scientific leaders in taking leadership positions on the global stage — not just the national stage.

Stephen Dupont: I thought what you said earlier was very interesting. You said: “We’re not going to be the generation making the world’s t-shirts.” So, is that partly why China is investing so heavily, for example, in Africa? Where just as in our country, for decades, we went to Asia to find cheap labor to make our stuff, now China, which has reached economic parity with the U.S., is searching out developing countries that can make its t-shirts?

Zak Dychtwald: That’s part of it, but it’s not just Africa. I think the main reason that China is investing in Africa is that the rest of the world has not or will not. (Note: See this article from Forbes for further insight about China’s investments in Africa). For example, when Trump came to power, he ordered the retraction of a good amount of aid that the United States is putting into Africa.

But even before that, people weren’t really trying to help Africa. Yes, sure, they built roads from the rubber plantation to the ports where it could be shipped out. But they weren’t really trying to build the infrastructure of Nairobi, for example, which is what China is doing. China is creating real deals in Africa that Africa needs. At the same time, what’s developing out of these economic dependencies has a lot of the world sort of crying neocolonialism. I think that’s BS, but – China is looking at places that need help, that are third-world and developing, and providing that sort of economic assistance and economic reliability that a big buyer can bring to any smaller country, smaller economy.

Other countries are starting to understand what China is doing. The Belt and Road Initiative is a good example of this. China is creating a web of dependencies, a hub-and-spoke model of dependencies, if you will. Where it’s the hub and there are 70 spokes — 70 countries whose economies will be linked into China’s.

This is not just supply chain stuff, and it’s not just energy security for China (there’s a lot of energy-rich nations that China is pulling into this), and not just food security. With a hub-and-spoke model involving 70 countries, if any of those spokes breaks (economic or political relationships falter), the wheel keeps turning. But if the hub is removed, the wheel crumbles. So, China is putting itself at the center of an economic web of dependencies that also has massive political implications. It’s not just locking up the supply chain so that they can still be a part of the semiconductor trade, or even the shirt business when a lot of that goes to Vietnam and Bangladesh, but it’s also so that they can play an integral part in the world that will find it increasingly difficult to operate without them. That’s what they’re doing right now.

Stephen Dupont: Going back to the chess and checkers, it also means that the United States is really not part of that economic web, right?

Zak Dychtwald: This is the hard part about Belt and Road Initiative — and India, by the way, is freaking out about it, too, because their really not part of that web, either — for the United States, China is investing heavily in the smaller countries around it, recognizing that a critical mass, more than just any one thing or any one place, is likely going to give them the security they need.

China shares borders with 12 countries. I think we forget about this. Back to our nuclear conversation: you’ve got Russia to the north, and you’ve got sort of a crazy person in your backyard with North Korea. We imagine that China’s pulling the strings on North Korea, but, I mean, there is no one more afraid of a totally nuclear North Korea than China.

It’s incomparable to the fear we might feel in the U.S. You have India and Pakistan, who have nuclear programs and have had their own historic skirmishes, and China has had skirmishes with both.

So basically, from a Chinese viewpoint, you kind of feel surrounded by many unfriendly faces. The best way to ensure long-term peace is to sort of graft these countries to you. And so, no, that doesn’t include the United States, particularly as we’ve shrunken away from the region in recent years.

Stephen Dupont: How do young Chinese consumers look at brands? So much of our world revolves around consumer spending, and I wanted to ask you, are they developing their own consumer brands? Do they love American consumer brands like Starbucks, for example? And do you see a day when Americans will want consumer brands from China?

Zak Dychtwald: They like American brands. Starbucks is a great example. Apple, too. Apple sells more phones in China, despite having far less market share than in the United States. Young Chinese love our movies and our fashion. And there’s a tremendous want for those from within China. As the sheer volume of desire in China and economic capacity continues to rise, the desire for U.S. brands keeps growing. (Note: Read this article from Forbes about the most relevant brands to young Chinese consumers.)

Chinese Millennials are not buying the gaudy, loud brands, such as the huge Gucci belt or the leopard-print Lamborghini. Among the older generation, this trend that I call “face over function” is important. It’s the idea that something, such as a fancy car, gives you face — allowing you to socially posture – and is more important than what the product actually did.

Instead, Chinese Millennials are looking to belong to something and also individuate at the same time. What the heck does that mean? Let me first give you some context: there’s nothing more alienating than being a young person alone in a Chinese city. Ten million people moving all around you, cramming onto the subway, going to work, all trying to find their own place in that world. There’s nothing more isolating than that, honestly.

Now, add to that the perspective that most of China’s young people are single children. There’s a real want to belong to something. So, it’s a conflicting feeling: it’s wanting to be your own person but also wanting to belong to something. So, in China, young people are seeing brands as a way to form their own tribes.

To me, it’s reminiscent of the Ralph Lauren era in the ’60s — this idea that there is this refined brand, and if you wear that brand, you belong to something. Or, what you might see now with those who wear Nike. To young Chinese, wearing these brands is signaling to others that they live a certain lifestyle. These brands help young Chinese connect by making bigger statements, such as: “I’m the kind of person who owns an iPhone. What does that say about me? I’m urban. I’m educated. I have a certain type of job. I want a certain type of lifestyle.”

For the young Chinese person who wears Nike, they’re saying: “I’m a Nike person. I only wear Nike stuff. I run. I’m healthy. I’m dedicated to living a type of lifestyle that’s offbeat, that’s committed to health and fitness.”

By the way, the idea of going to run outside is totally new in China. Everyone thought you were a crazy person 15 years ago if you ran. But Nike has built a whole culture around it in China. If you look at the number of people who signed up for the 2008 Shanghai Marathon, there were maybe 50 people at the starting line. This year, there will be 30,000 people. What Nike did was build a community around it, and now everyone and their mother is lacing up for these long runs – it really is a massive shift.

Look at Supreme. It’s a skateboard, hip-hop brand from New York that has become really popular among young Chinese. Why’s that? Well, it’s because there’s a Chinese show called The Rap of China that was averaging 200 million views per episode. It’s not like Jay-Z and Kanye came and made this popular. No. It was Chinese rappers who are creating their own art with their own lyrics, whose narratives are speaking to the Chinese people rather than to people in inner-city United States, or rural United States, or wherever. While they were speaking to young Chinese people, they were wearing Supreme skateboard apparel because that’s something they identified with. So now, it seems every kid in China identifies with Supreme.

So it’s like a mixture of Chinese style and Chinese sensibility with a touch of foreign influence.

Stephen Dupont: What’s been the impact of the single-child rule in China. Isn’t there a significant gap between the number of males and females in China? What impact do you think that will have in the years to come?

Zak Dychtwald: Yes, there is. It’s a huge gap. There are roughly more than 30 million males than females in China.

Here’s the thing, though. China is still very traditional in the way that it dates. So it’s likely that these men are likely the poorest and the least educated in the country, and that has some leaders in China worried. There’s a parallel to what we’re seeing in the United States with our shooting issue: there is no more destabilizing force than single men who feel like they deserve to have a woman in their lives.

So China is tracking this. Some people are saying these men would make for good military fodder. But, if China is moving towards autonomous technology, maybe that’s not the solution.

An interesting solution to this problem came up during a recent conference call that I participated in. In China, you have this massive number of people who are entering old age, and China has the tradition of a barefoot doctor — a man who doesn’t have a formal medical background, but knows how to treat patients in rural and semi-rural places.

The suggestion has been made that maybe these young men who are having trouble creating families because there are too few women could become caretakers for this older generation, or possibly the government will incentivize them to become caretakers for the elderly throughout the country. When I heard this, I thought that was a pretty cool solution. I had never heard that before. But, you know, thinking from a futurist mindset, what do you with 30 million unmarried men who feel like they deserve a woman in their lives, and if they don’t get that, may lash out at society? Well, maybe you employ them, give them a great job, and give them a community along the way. That, to me, is a pretty far-out solution to what is one of the major problems facing China over the next several decades.

Stephen Dupont: So, if you could give just three pieces of advice to American business people in how to approach China over the next 20 years, what would you suggest?

Zak Dychtwald: Three pieces of advice…well…I’d like to offer three pieces of cautionary advice.

Zak Dychtwald: Three pieces of advice…well…I’d like to offer three pieces of cautionary advice.

First, don’t expect modernization of China to mean Westernization.

Second, recognize that China has a totally unique culture, identity, and way of looking at the world, and they’re proud of that.

And third, to build on that, what makes China really unique is that it’s culture and identity drive its economics and politics.

They’re all linked up to this idea of culture and identity, but it really is all underpinned by the importance of caring about the people, of understanding the narrative, understanding the culture, and recognizing that all of these creates a unique sort of economic, political, and business outcomes different than anywhere else in the world.

Stephen Dupont: For those who want to learn more about China, what would you recommend in terms of reading, documentaries, etc. – besides your book, Young China, which I would highly recommend?

Zak Dychtwald: I would recommend subscribing to Bill Bishop’s Axios newsletter Sinocism for the political side. SupChina, SixthTone, and Jing Daily also have less political, more cultural offerings. I would also recommend A Billion Voices: China’s Search for a Common Language by David Moser for insight into how modern Mandarin was formed.

Stephen Dupont: If you only had 10 days to travel throughout China and get a sense of the new generation that is rising there, where would you go?

Zak Dychtwald: For a ten-day trip, I would do a quick stop in Shanghai, a bullet train to Beijing, and then a flight out to Chongqing. These three cities will give you a pretty cool view of China if it is your first time. If you’d like to get out in nature a bit more, go to Yunnan Province and Guilin.

Stephen Dupont: My final question: Would you recommend to American parents that instead of having their kids learn Spanish they should be learning Mandarin Chinese?

Zak Dychtwald: Absolutely. Without a doubt. There is no generation, anywhere in the world that I believe will be as impactful as China’s Millennials and Generation Z. Period. I’d love to make that argument for American Millennials, and there’s an argument to be made there, but we’re talking about real parity.

Second, the greatest gift I’ve ever given myself is learning Chinese. From a pure intellectual point of view, it feels like I’ve built an entire different world in my brain — like I’ve doubled the size of my brain through my cultural immersion into Chinese. There’s different colors, landscapes, and features, and – just from the way that that can stimulate a young person’s brain and the way that they see the world is a true gift.

This is not to say Spanish isn’t great, or that the Spanish-speaking cultures that impact America are not wonderful. But, if you want to give your child a different view of the world, Mandarin is an incredible option.

Stephen Dupont: Zak, thank you for taking the time to talk with me and share your insights about young China.

Zak Dychtwald: You’re welcome.

Note from Stephen Dupont: Here are some additional resources to learn more about the economic growth of China:

https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/china/what-can-we-expect-in-china-in-2018

Stephen Dupont, APR, is VP of Public Relations and Branded Content for Pocket Hercules (www.pockethercules.com), a brand marketing firm based in Minneapolis. Contact Stephen Dupont at stephen.dupont@pockethercules.com or through his LinkedIn page: www.linkedin.com/in/stephendupont.

© 2018 by Stephen Dupont