Know, Like, Trust and Creating Value: Conversation with Speaker, Author and Sales Expert Bob Burg

By Stephen Dupont, APR

“All things being equal, people will do business with, and refer business to, those people they know, like, and trust.” – Bob Burg, author, Endless Referrals

I think I picked up Bob Burg’s influential book, Endless Referrals, about five years ago after interviewing speaker and sales consultant, Kevin Knebl, co-author of The Social Media Sales Revolution, for an article I wrote on how to use LinkedIn more effectively. Kevin pointed me to Bob’s unique concept about networking and building a business through referrals: “All things being equal, people will do business with, and refer business to, those people whom they know, like, and trust.”

I was immediately captivated by his thinking, and eagerly gobbled up his next book, the Go-Giver, which spoke to the power of this concept: “Your true worth is determined by how much more you give in value than you take in payment.” Co-authored with John David Mann, the Go-Giver series of books have sold more than 800,000 copies and have been listed on numerous bestseller lists.

If you haven’t heard of Bob Burg, he is a highly regarded sales and business consultant who has spoken to many of the nation’s top companies, franchises and business associations. To learn more about Bob, I invite you to check out his website, burg.com, and to listen to his podcast, The Go-Giver Podcast, which features interviews with business leaders and entrepreneurs.

Recently, I reached out to Bob to see if I could interview him for my blog, stephendupont.co. I’ve always wanted to speak to Bob about his concepts of doing business in our digital age, and he gladly accepted.

In this interview, I ask Bob to share insights about the key sales and business concepts that he has developed, as well as to comment on a number of questions that I have been pondering, such as doing business in a time when so many people would rather communicate through social media and emails, or understanding what value humans will offer in the years to come when increasing amounts of our work is automated with artificial intelligence.

Stephen Dupont: Bob, your new book, The Go-Giver Influencer, co-written with John David Mann, was recently published, and it’s the fourth book in this very successful series. How does it expand on the Go-Giver book series and why do we need this book now?

Bob Burg: Influence has always been a part of the Go-Giver book series.

In the first book, we spoke about the Law of Influence, and in our next book, the Go-Giver Leader, we explored influence and leadership. And of course, the two are inextricably related.

We decided in this book that we wanted to take the concept of influence and drive deeper into it.

We really believe that at this stage in our nation’s history, we really need people who can learn how to influence, and influence in the correct way.

You know, we’re seeing a real breakdown in communications and civil discourse – between family members, among friends, among co-workers, in our media, among our nation’s politicians, and among the tens of millions on social media.

Today’s discussions are really no longer discussions, but rather fueled-up, hate-filled vitriol spewing diatribes and personal insults.

The result is that minds are not changing. If anything, they’re remaining even more stuck in the echo chambers of their closely held beliefs.

Friends are becoming enemies. Discourse has all but shut down. Understanding and acceptance is not being reached. And people are feeling lousy about it. I think if you were to ask the question of most people, “Would you like to see people communicate more civilly?” they’d say, “yes.”

But, aside from just communicating more civilly, we need to be better equipped to communicate more persuasively and influentially to help others better understand and accept our ideas.

Stephen Dupont: What do you think is the influence of social media and other technology on this process of building dialogue with others?

Bob Burg: The idea of social media is great, in that it opens up new worlds. It democratizes communications, allowing anyone to communicate their viewpoint. But, on the other hand, because anyone can communicate their viewpoint, anyone does. Often times, those with the loudest voices, spewing vitriolic insults tend to know the least about what they’re talking about. I think that’s a universal law of life (and I suspect that it’s always been that way), but with social media, there’s a platform that allows so many more people can do that.

The opportunities that social media offers are immense — to connect with one another, to communicate with one another, to grow from each other, and to learn with one another.

But, it also creates the opportunity for people to do lousy things, too. What we’ve seen is that as it becomes more acceptable to take a side or to argue for a team, it’s becoming more difficult to arrive at the truth. More and more, we’re seeing that if “you don’t agree with me,” people are going beyond saying, “you’re wrong” to saying “you’re evil.”

By and large 97% of the people want good things to happen. But what happens when we see people defending their team (such as a political party with whom they’ve associated), it’s not the truth they’re defending, but their team. I don’t think that’s helpful for the individual or for their team. And I don’t think it helps society, either.

Social media can accelerate this, but it isn’t to blame for it. After all, it’s just a tool. What I think we need to do is start expecting more of each other, and of ourselves. That’s where the responsibility lies.

Stephen Dupont: In a recent Go-Giver podcast, you interviewed leadership motivational speaker Bill Wooditch. One thing that struck me about that conversation was the need to understand one another, and to seek to be understood. Many people want to create win-win relationships with each other. How important is it to do our homework in learning about each other, and listening carefully to one another to understand?

Bob Burg: A big part of that, and you mentioned “seek to be understood,” comes from Dr. Stephen Covey, author of The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People, who said: “Seek first to understand, then to be understood.”

I think that is very correct. That is the order in which we need to do it. Similarly, in the Go-Giver books, we say, “You provide value before you receive the income” or “you sow seeds before you reap.”

It’s the same with listening, understanding and communicating.

One of the things we say in our book, The Go-Giver Influencer, is “put yourself in other person’s shoes.” Now I know that sounds easy and maybe even trite because it’s a saying we’ve heard for years. But here’s the thing: It’s not necessarily easy to step into another person’s shoes realizing that most of us have different size feet.

In other words, we all come to the world from different belief systems and different perspectives. We have our own subjective truths and our own paradigms. We don’t necessarily know what another person is thinking, but as human beings, we generally think that people see the world in the same we do. But that simply isn’t true.

So, the only way we can really place ourselves in another person’s shoes is by asking questions, and then, listening. In our latest Go-Giver book, the character Coach tells his protégé, “Listen not just with your ears – because that’s surface listening. It’s how most of us listen, because that’s listening so we can talk (get our point of view across). Instead, the Coach says: listen with your eyes, listen with your posture, and listen with the back of your neck. In other words, listen with your entire being; your entire essence.

The reality is that’s really difficult for most of us. But when we do listen with our entire being to another person, it’s amazing what happens. It allows us to really understand another person.

Listen, sales is simply the process of discovering what another person needs, wants or desires. The only way you’re going to discover that – because you can’t read their mind – is to ask questions and listen intently.

The other thing when you do that is the other person feels listened to. They feel understood. That’s a very basic human need. And when that happens, a person starts to trust the other person.

Stephen Dupont: From the many informational interviews and coffees that I’ve done over the years, I’ve seen a lot of people struggling with the concept of success and purpose. They want to be successful (and they may already be successful, based on how our culture defines it), but they also want to feel like what they’re doing matters.

How do the principles (the Laws of Stratospheric Success as you call them in the Go-Giver books) apply to helping a person understand their purpose (or Knowing your Why?) and knowing what to do with their lives and doing what matters?

Bob Burg: I think when it comes to finding our why, it’s a constant process for most people. Yes, you hear those stories about people who know exactly what they wanted to do from a young age, but I think those stories are not typical.

I think we find our ourselves, and our why, along the way. It tends to be a combination of what you’re naturally good at, and what you enjoy doing or what you’re passionate about. It seems to me that that’s how we were created. I think we’re all naturally inclined to different things. Some people are naturally gifted when it comes to athletics; others toward other things such as math, communications, or leadership.

It tends to be that what we’re gifted at, we’re also good at. That’s not all the time. But it happens a lot. So I think you need to look at the nexus of what your natural talent is and what you enjoy doing. When that’s the case, you’re much more likely to work at it. Keep this in mind: even a natural athlete has to put a ton of effort into what they need to do.

If you’ve read Malcolm Gladwell’s book Outliers, which introduced us to the concept of the “10,000 hour rule” (originated by Professor Anders Ericsson), we learn that you don’t become a master or an expert by simply putting in 10,000 hours of practice. It’s actually, 10,000 hours of deliberate, intentional practice. That’s quite a bit different.

What that says is to really master something, you need to put in a lot of time and a lot of deliberate effort. But to do that, I think, you have to enjoy it.

Now, to make a living out of it — to take something that you love and make a living at it — you need to take it one more step. There’s an old saying, like many old sayings, which is half-true. It’s: “Follow your passion or follow your bliss and the money will come.”

It’s only half true because you have to find a market – someone who is willing to pay you for what you offer. You need to communicate sufficient value for what you do and what you love. Because if you’re unable to do that, what you wind up with is a hobby.

There’s nothing wrong with hobbies, but if you want to make a living from what you love to do you need to connect it with what the market needs and wants.

Stephen Dupont: One of my takeaways from your recent Go-Giver podcast interview with Alex Banayan, author of the new book, The Third Door, is that so many people, when they think of success, look up. We look up to Bill Gates, Warren Buffet, Quincy Jones, Lady Gaga, as the pinnacles of success.

And yet, we forget or overlook that there is incredible wisdom to be gained about living a rich and fulfilling life from those around us – from our parents, our friends, from people who may not be as successful as those famous people I mentioned. Could you comment on this – about not overlooking the wisdom and abundance that may already be in front of us?

Bob Burg: The sages asked, “Who is a wise person?” And they answered, “that person who learns from all others.”

To me, what that says is we can learn from anyone and everyone. From those right around us, to those we have studied from history, or experts we interview. In other words, everyone has wisdom to share or lessons to share.

I remember Jim Rohn (author of 7 Strategies for Wealth & Happiness: Power Ideas from America’s Foremost Business Philosopher) saying: “You can learn from anyone. From some people you learn what to do, and from others, what not to do.” I agree with that, because there have been plenty of people in my life that I’ve learned what not to do. And that was valuable to help me grow.

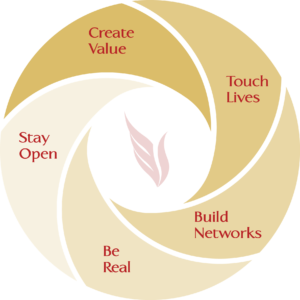

I think the big thing is to keep learning. In our Go-Giver books, we speak about the Law of Authenticity, which says: “The most valuable gift you have to offer is yourself.”

I think authenticity, like the word influence, can often be misused or misinterpreted these days. Authenticity can be confused with not growing. In other words, a person says, “I am what I am, and I’m not changing,” or “I have anger issues and that’s why I yell, and if I do something differently, then that wouldn’t be authentic.” Well, that’s just silly. That just means they authentically have a problem to work on.

When you truly accept your authenticity, you step into the highest level of your authentic self possible.

There’s certainly something to be said to seek wisdom from those who we feel are more successful than us (financially, health wise, career wise, emotionally, spiritually). I try to seek out wisdom from those who are more successful than I am. It only makes logical sense. But I believe that you can learn from anyone and from any and every interaction.

Stephen Dupont: In our digital age, I see more and more people using technology such as social media or email to conduct business. One of the things that struck me about Alex Banayan’s book was that he sought to meet people like Bill Gates face-to-face. Certainly, he could have conducted those conversations over the phone, like you and I are doing now. How important is it to still meet with people face-to-face to develop relationships and conduct business?

Bob Burg: That’s such a great question. And it’s so cool that you noticed that with Alex. I still think, all things being equal, that face-to-face meetings are the best way to build relationships and conduct business.

At the same time, I don’t think it’s an either/or question. I don’t think it’s face-to-face or through technology. I think both are good and both add to the other. Certainly technology offers us the opportunity to meet more people than we ever could have beforehand.

I also do think that true win-win relationships can be built over social media.

The first time I really understood this was when I would interview people for my blog (before my podcast), and I asked Dondi Scumaci (author of the bestseller, Designed for Success: The 10 Commandments for Women in the Workplace) if I could interview her. I loved following her tweets, so one day I reached out to her through her Twitter page. At that point, we had never met.

So we got on the phone and started talking like old friends and I asked, “By the way, have we ever spoken before?” and she said, “No, I don’t think we have.” So there’s a case where social media helped us to get to know one another really well before we actually spoke with each other over the phone. And since then, we’ve interviewed each other and we’ve spoken at each other’s events. So, technology is a great tool in building relationships.

But if it’s a yes or no question, all things being equal, I would say “yes,” I believe face-to-face meetings are definitely a step above building relationships online.

Stephen Dupont: In your Go-Giver book series, you use the stories of Joe, or in your most recent book (The Go-Giver Influencer), Jackson Hill and Gillian Waters, as a vehicle to share your principles of success. How important is storytelling to influencing and persuading people (to buy a product or service, to cast a vote, to make a donation, etc.) and do you have any recommendations on how professionals should incorporate more storytelling into their sales process?

Stephen Dupont: In your Go-Giver book series, you use the stories of Joe, or in your most recent book (The Go-Giver Influencer), Jackson Hill and Gillian Waters, as a vehicle to share your principles of success. How important is storytelling to influencing and persuading people (to buy a product or service, to cast a vote, to make a donation, etc.) and do you have any recommendations on how professionals should incorporate more storytelling into their sales process?

Bob Burg: One thing I’d like to mention in answering this question is that my co-author for the Go-Giver books, John David Mann, is a gifted storyteller. He’s really the lead writer and storyteller. I’m much of a how-to kind of person.

Now, when I speak on stage, I tell a lot of stories, but those are stories that give examples to illustrate a point. They’re true stories.

With the Go-Giver books, we’re using parables to get our message across. We’re sharing truths based on real life using fictional stories.

I think storytelling is more important than ever before. Keep in mind, history, for a long time, was communicated through an oral tradition. So story telling has always been important. But I think today storytelling has taken on a different level of importance. That’s because there’s so much information out there. The question is how do you get through – how do you capture the attention of people. I can tell you, it’s usually not through facts.

There’s an old saying. And again, it’s another one of those sayings that’s half-way true: “Facts tell, stories sell.” I learned through John that it’s not necessary that stories sell, it’s that they connect. They connect with people on a heart-to-heart level. When you make that connection, then you can sell. Meaning your ideas, your product, your service, your concept, or your idea.

As I mentioned, “all things being equal, people will do business with — and are willing to be influenced by — people that they know, like, and trust.” And I would say this happens more quickly through stories than through any other way.

Stephen Dupont: In this age of the Internet, many people or organizations do a great deal of research on their own about what they need to solve a problem, including research on specific products or services. Because of this, the solutions-selling approach is becoming less effective some say (Harvard Business Review: The End of Solution Sales) and is being replaced by a new approach, insight selling (influencing a potential customer as they’re researching what they need).

Then, we have your approach, as I see it, as in value-selling, based on your principle from your Go-Giver books, “Your true worth is determined by how much more you give in value than you take in payment”? Is that a fair assessment? Is value-selling the next evolution in selling and persuasion?

Bob Burg: Well, in a sense, I think they all come together. They all mesh. Remember, value is a relative worth or desirability of a thing; of some thing: this product, this service, this concept, this solution or this insight that brings so much worth to someone that they’re willing to exchange their money for that.

They’re also exchanging their energy, their time, and their lost opportunity (of doing business with someone else), and that through this choice, the solution won’t be too disruptive to their business. It’s always key to remember that value is always in the eyes of the beholder. It’s not what we find of to be of value, it’s what the customer finds of value.

Now, if you’re talking about solution selling, you’re helping a person come up with a solution, or you’re using your product to help someone find a solution, I think that’s what selling has always been. It wasn’t always done effectively, especially when the focus was on the hard sell.

Could you be successful that way? Well, sure. But it’s usually not sustainable. And you had to work really hard.

Now as sales become more sophisticated, we started to realize that people aren’t just buying a product or service, they’re buying a solution to a problem – or something that will bring them joy or happiness.

So it’s not so much that solution selling has been replaced, but added onto. The first person who wrote about this was Neil Rackham, who wrote the classic, SPIN Selling. It’s not spin, like we use to describe political messaging.

Neil defines SPIN as S for understanding the customer’s Situation; P, the customer’s problem; I, the implication of that problem; and N, the needs payoff.

It’s a masterful book written 30 years ago. It’s for the more complex sale, where there may be a lot of moving parts. Then about five or six years ago, another book came out called The Challenger Sale, by Matthew Dixon and Brent Adamson. It picked up on where Neil left off. It was another great book.

What both of them talked about was the concept of insight. Anticipating a customer’s problem before the customer recognized it as a problem. The sales person understands so much about the customer’s person’s problems that they can come in before those problems emerge and create opportunities.

Stephen Dupont: When I think about brands, I think that people gravitate to brands that align with their own personal values – and that serves as the basis for long-term brand loyalty. In the Go-Giver series, you speak of giving more in value than you take in payment, but how does aligning your values with those of your customer matter? If your values don’t align with a customer, should you not bother trying to influence or persuade him/her to see things your way (or buy your product/service)?

Bob Burg: There’s something I’d like to differentiate here. There are values and there is giving value.

In this case, values are the morals, mores, or operating principal mindset, or culture.

By the same token, a company’s values can hold value to a customer.

By way of example, let’s say Company A has certain political feelings about something. And there’s another company, Company B, that needs a product or service offered by Company A. Well, Company B may find the values of Company A so disturbing that they refuse to do business with them. Those values outweigh any potential value that Company A might offer. But, for another company, they may completely disagree with Company A’s philosophy or approach, but still do business with them. They like the product and let Company A stand for whatever they want.

Again, it goes to value – the relative worth that a company finds in another company’s products or services.

It can go the other way, too. A company may choose to do business with another company because they respect the values of that company so much that they’ll choose a relatively lower quality product over a higher quality product made by another company.

To the degree that we have a free market, the customer chooses a product or service based on the value they perceive.

Stephen Dupont: I’d like to go back to your concept about “know, like, and trust,” which is widely quoted (or misquoted!). Here’s the actual quote: “All things being equal, people will do business with, and refer business to, those people they know, like, and trust.”

In an age where our trust in many institutions is being tested (government, corporations, media, etc.), how important is the role of trust in this formula?

Along these lines, I wanted to ask you about consistency, too. How important is it for someone to develop their consistency?

Bob Burg: So, in terms of trust, it’s even more important than ever before.

We have so much media out there that are trying to attract eyeballs. It’s their job. I’m not here to make a value statement about media, but often times they do stories that are not flattering about business or business leaders in order to attract the eyeballs.

A headline that does not sell is: “CEO Takes Great Care of Company’s Employees.”

A CEO or a business doing something bad, does.

In Daniel Kahneman’s magnificent book, “Thinking, Fast and Slow,” he talked about the effect of when we see something a lot, we perceive that it’s more prominent than it really is.

So, because we see so many more stories about leaders who are not to be trusted, we think that all leaders are not trustworthy. And that people in general are untrustworthy. It can very easily be said that we currently live in a low-trust society. In reality, I don’t think that’s really changed over the years, but because we see all of these negative stories, we perceive it in that way. We’re probably dealing with a continuum. A small percentage of people are 100% trustworthy. A small percentage are 0% trustworthy. In between, most people are mostly trustworthy, perhaps 75% to 80% of the time. That’s just an observation.

We live in a low trust society. Surveys and research have proven that.

The good news is that a company or a person who is able to communicate their trustworthiness – their worthiness of being trusted — is nine steps ahead of the game in a ten-step game.

Stephen M.R. Covey, the son of Dr. Stephen Covey, author of The Speed of Trust, breaks trust down into two categories: competence and character. Both are important. You can trust someone or a company’s character, but if they’re not competent, you’re not going to do business with them because they won’t be able to do the job to deliver sufficient value to you or your organization.

And vice versa. You can believe that a person or a company is very competent, but if you don’t trust their character, you won’t be doing business with them because it’s simply too risky. There’s too much to lose.

I absolutely believe that trust is critical today. And it’s something that today’s business leaders need to focus on — earning the trust of their employees and their customers.

Consistency is an important ingredient in the recipe of trust. This goes back to the caveperson days, when literally, every day was a life and death struggle. Because of this, consistency was important – you had to know who was who, and who did what. You had to have an agreement of what something meant. One mistake could mean death. So, when you went out to forage for food, you had to know what a bent twig left by another member of your tribe meant. It needed to mean the same thing every time.

Consistency is treasured by people in others. This is why I think fast-food restaurants are a role model for us. It’s not necessarily because the food is the best but the same, and you can count on how the food is delivered, how clean the restaurants are, where the soda machines are, how clean the tables are, etc. You feel safe.

Stephen Dupont: Another question about your “Know, Like, and Trust” formula: Does it need to be implemented in a linear process – someone has to get to know you first, then like you, and then trust you – or can it happen all at one time?

Bob Burg: I think “Know” comes first, only because you have to know who they are before you can like and trust them. You don’t necessarily have to know them well, but you have to know who they are. I think the other two are a little less linear. After all, you can trust someone without liking them.

Now, all things being equal, the person you know, like, and trust will get the business versus the person you know and like or know and trust. So, if a company is the only game in town, and you can reasonably trust them, you’ll do business with.

But, there’s a good chance that you’re not the only game in town. And therefore, if there’s someone who offers what you do, then a customer will do business with that other company if they know, like, and trust the other company more than your company.

So the key here, and this is where I am often misquoted, is the focus on the “all things being equal” or “close to equal.” Because when they’re not equal (or at least close enough to equal), “know, like, and trust” loses the power.

Stephen Dupont: As we look into the future, many futurists and foresight experts are forecasting a time when many jobs will be eliminated because those jobs can be performed less expensively with robots and artificial intelligence.

What do you think will be the key for people to stay relevant (and employable) in the future?

Bob Burg: I think this is very important. If you go into my Go-Giver podcast archives, you’ll find a podcast interview with Geoff Colvin, author of Humans Are Underrated.

The basic premise of the book was that we used to ask, “What can humans do that machines can’t do?” and we used to be pretty safe. Today, he says that question is no longer relevant, because basically technology can do just about everything that humans can do, and in many cases, even better than humans. And that’s not going to stop.

Now we will ask: “What can human beings do that consumers will not accept from technology, but will only accept from human beings?”

His book was absolutely brilliant. He points out that the most highly valued skills of tomorrow are what we call “soft skills” – empathy, leadership, teamwork, collaboration, kindness, emotional intelligence – that’s what going to keep a person relevant. Because while AI can do many things, it won’t be able to do these things – the soft skills — as well as a human being.

Stephen Dupont: Knowing what you know now, if you could give your 18-year-old self any piece of advice, what would you tell him?

Bob Burg: Yes, this is actually a very easy one for me. “Burg, you don’t know half of what you think you know.”

It reminds me of the old saying often credited to Mark Twain (though he didn’t actually say it, it sounds very…Twainian): “It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.”

That was me when I was 18. Actually, that was me until I was 22 or 23. I just thought I had it figured out. I thought I understood human nature. Why people thought as they did. How the world worked. What was good and what was bad. And I just “knew it.” And I made a lot of mistakes.

So, that would be the advice: If Old Burg could go back in a DeLorean and have a heart to heart with Young Burg, that’s exactly what I would say.

Stephen Dupont: You brought up the word “mistakes,” how important is it to embrace your mistakes and learn from them?

Bob Burg: It’s very important. The wise person learns from their own mistakes. The really wise person learns from the mistakes of others.

So, learning from our own mistakes is a good thing, but not if we could have learned from the mistakes of others and avoided those mistakes in the first place.

We’re human and certainly we are going to make mistakes. To the degree we can learn from them and not repeat them, we’re on the right track. If we’re making those same mistakes and we’re getting lousy results, we owe it to have a heart to heart with ourselves or with someone we trust, and ask them, “What we’re doing wrong.”

Stephen Dupont: Thank you Bob for sharing your wisdom.

Bob Burg: My pleasure.

Stephen Dupont, APR, is VP of Public Relations and Branded Content for Pocket Hercules (www.pockethercules.com), a creative brand powerhouse based in Minneapolis. He is a frequent contributor to PRSA’s Strategies & Tactics and Forbes.com. Contact Stephen Dupont at stephen.dupont@pockethercules.com or visit his blog at www.stephendupont.co.

© Stephen Dupont, 2018